By Michael Bugeja, IOWA CAPITAL DISPATCH

Back off! Social distancing was already a problem before coronavirus. (Photo by Getty Images)

Do you remember thriving downtowns, even in rural areas, with cafes, diners, restaurants and maybe even lunch wagons; hardware, clothes, book and department stores (some with lunch counters); TV-, car- and shoe-repair shacks; smoke, pet, barber, beauty, music and antique shops?

Then the mall opened. Maybe a Walmart superstore, and slowly several of those hometown landmarks went bust.

For more than a quarter century, megamalls had served as the main gathering place. Then came Internet and online shopping with eBay and Amazon, sparking a retail apocalypse.

In 2016, J.C. Penney, RadioShack, Macy’s and Sears each closed more than 100 outlets. Every year, one after the other, major chains filed bankruptcy. In 2019 alone, more than 9,300 popular stores shut their doors, the biggest year ever for closings, according to Yahoo Finance.

The exodus from physical place affected houses of worship. By 2018, Gallup found at an all-time low the percentage of Americans who belonged to a church, synagogue or mosque. Only 50 percent of respondents attended services, down from about 70 percent between 1937 through 1999. The drop-off intensified in the ensuing 20 years.

People were disappearing altogether. Parks and libraries often were empty. Children played video games, patrons checked out eBooks. Teens texted into the wee hours in locked bedrooms. Adults ran apps on androids instead of laps in recreation centers.

By 2018, Americans were spending 11 hours per day looking at screens instead of each other. Factor in six hours sleep, and that’s 75 percent of waking hours.

The great outdoors used to mean nature — hiking, gardening, bird-watching, swimming, fishing and hunting. It still means that for some of us. But for many, the outdoors came to mean simply leaving houses and offices, navigating physical space in cars the way a submarine navigates the sea.

And yet, some downtown stores managed to survive. Some malls stayed open. Churches, synagogues and mosques welcomed the faithful. Parks and libraries were maintained, and community centers provided meeting spaces.

When we needed a break from social media, we could stow smartphones and wander the half-closed Main Streets and malls. We soul-searched on occasion with congregations. We relaxed in parks, exercised in gyms and patronized Ticketmaster for large gatherings at concerts and sporting events.

In this election year, political rallies were attended by hundreds of thousands.

Then came the coronavirus, and everything stopped, closed, or was banned or canceled.

The coronavirus has demon-like characteristics. You can have it with no apparent symptoms and spread it within close proximity of a neighbor. It takes a while to activate within a carrier, so you can test negative on a Tuesday and still spread it on a Thursday.

There are many fears in this life. Top ones are known by the suffix “phobia,” as in acrophobia, fear of heights; claustrophobia, fear of enclosed spaces; entomophobia, fear of insects; ophidiophobia, fear of snakes; astraphobia, fear of storms; and trypanophobia, fear of needles.

But of all the terrors, one in particular is the most intense in all of us: fear of the unknown.

Coronavirus taps into this, triggering panic behaviors.

Handshakes, a symbol of peace tracing back to the 5th century B.C., are forbidden. Yes, for good reason, because the virus is apt to be there. Even President Trump has found it hard not to extend a hand. At a news conference about the coronavirus, the Washington Post reported that the president continued “to shake hands with other speakers, many of whom are members of the White House Task Force charged with trying to stem the disease.”

Because of the emphasis on hands, sanitizers quickly vanished from store shelves. Hoarders bought crates of them. According to the New York Times, one Tennessee man bought 17,700 bottles to sell at exorbitant prices on eBay and Amazon before those online companies prohibited him and others for price gouging.

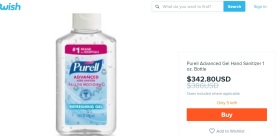

Nevertheless, I checked Amazon on March 15 and found one seller “discounting” a one-ounce bottle of Purell sanitizer for $342.80.

Nevertheless, I checked Amazon on March 15 and found one seller “discounting” a one-ounce bottle of Purell sanitizer for $342.80.

Things are going to get worse before they get better. But they will get better. Sooner or later, a vaccine will be developed, and we can all go about living our digital, cloistered lives.

Maybe.

For almost two decades, I have documented the erosion of community because of technology, noting how it would change culture and, ultimately, ethical values established in time, place and society: truth-telling, fairness, responsibility and civility. I am not optimistic.

The coronavirus has set a dangerous precedent — that everyday human contact can be deadly. As such, social distancing will continue as long as we can be distantly social on Facebook and Instagram.

The real challenge for the multitudes who will survive this scare is learning to trust each other again, in person, with a handshake sans sanitizer. The alternative — continued, deeper, damaging self-isolation —may be the lurid legacy of this crisis.

We will need leadership at all levels of government as well as in our schools, churches, homes and work places to avoid that viral scenario.